Laura Maylene Walter's collection Living Arrangements won the G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize for short fiction in 2011. Her stories are lucid and unflinching, involving characters ranging from a creepy man obsessed with a champion figure skater to an unattractive underwear model who arouses local interest. Laura touches upon grief, lust and place with a steady hand, quiet language and underlying friction.

1. I remember reading the story of your winning the G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction on your blog. Would you like to recap?

Good things happen when you eat fatty bread, apparently, because I was busy tasting samples at an olive oil store in California (lauramaylenewalter.com) when I got the phone call that I’d won this contest and that my debut story collection would be published. Immediately after receiving the news, I ate some vegetarian tacos, went to a couple of wine tastings, and then hopped on a train bound for Oregon. It was a surreal day, to say the least, and it took weeks for the shock to wear off.

Many of the stories in Living Arrangements (lauramaylenewalter.com) were written at a time in my life when I wasn’t actively seeking publication. Instead, I was trying to improve and grow as a writer. I churned out story after story, workshopped them in various writing groups, and revised. It wasn’t until years later that I first considered entering a short story collection contest. I went back to all my old stories, decided they could work as a collection (and felt a bit surprised that I’d written an entire book of stories without even trying) and entered three collection contests that winter. Seven months later, I got the call that I won the Chandra Prize, and I’ve never looked at olive oil in the same way since. (Okay, that’s a lie.)

2. You've been writing short stories for years now, before Living Arrangements came out, what were your feelings about submitting work? Have you submitted a lot of work in the past? How did you deal with rejection? Do you think you are in a safer place now, having published?

When I was nineteen years old, I submitted three poems to The Paris Review and had the nerve to be both surprised and disappointed when they were rejected. (I still remember one of the poems. It was about an ice sculpture of a woman. I believe she was melting – need I say more?)

Despite a few overly optimistic moments like that, I wasn’t a stranger to the submissions process, even as a teenager. Back then, I sent my work to publications geared toward students and occasionally queried or submitted to markets advertising in writing magazines. At age 16, I received my first paying acceptance for a short story (the journal is now defunct). In my early and mid-twenties, I sent out a few rounds of short fiction submissions to journals and was soundly rejected. It was discouraging, but I knew deep down I wasn’t there yet and had a lot to learn. This is what set me on the path of just writing and revising without worrying about submitting. In the end, this paid off.

As far as feeling if I’m in a safe place now that I’m published – I don’t. I still feel like I’m starting from zero and, with a very few exceptions, am submitting to slush piles like everyone else. Rejection is just a fact of the writing life. (lauramaylenewalter.com)

3. I understand you're working on a novel now. Is that connected to Living Arrangements by way of themes or place or character? How do you feel about changing genre and where do you feel most comfortable?

I’m about halfway through the first draft of a new novel that represents a departure from most of the themes in Living Arrangements or my previous novel-in-progress, OPAL, which focused on a mother-daughter relationship. I don’t want to say much about the new project right now because I’m still in that elusive magical point (lauramaylenewalter.com) of the writing process and don’t want to spoil it. But here’s a hint: If you take some of that creepy-sexy-taboo darkness in my figure skater story (“The Ballad Solemn of Lady Malena”) and twist it with the voice of the narrator in “The Clarinet,” you’ll get something a bit similar to what I’m working on now. In other words: Like many writers, I can’t escape myself.

Honestly, I think I am still most comfortable with short stories, but there’s just something about working on a novel. It becomes a part of you for so long. But I love each form for its own reasons: for the small, contained world of a short story, which makes it so alive with possibilities, and for the more complex, long-reaching scope of a novel.

4. In the UK this year has been named Year of the Short Story by some (publishers and enthusiasts), although I've always thought there was a broader appreciation for short stories in the US. Do you think that holds true?

I can’t compare the short story’s popularity in the United States to that of the U.K., but at least from a publishing perspective here, short story collections are not money-makers and are therefore not nearly as sought after as novels. In fact, part of the reason I never envisioned my short stories being published together in a book is because I had it drilled into my head that short story collections don’t sell, agents aren’t interested in representing a collection if you don’t have a novel, and big houses don’t want your collection unless you’re already famous. (Thank goodness for small presses.) I can’t count how many times I’ve heard a writer say that an agent or editor tracked her down based on the strength of her short fiction only to immediately ask: “But do you have a novel?” It’s just how the business works.

5. Most writers' first collections bring together work that spans several years, would you ever embark on a themed or interlinked short story collection? Or do you think each story has to spring from its own well?

I’d love to one day write a linked short story collection. Right now, my new stories are not closely connected and develop individually, but I’m also conscious of how they might work together in a book. It’s different this time around because with every new story I write, I consider it not just on its own but as a potential part of a collection.

6. First person, second person or third person? You work with the second person very capably - not easy. Do you have a preference or a way of deciding which person to use?

I recently poked fun at the second-person point of view in a blog post, (lauramaylenewalter.com) but as anyone who reads Living Arrangements knows, I haven’t shied away from writing in this point of view. The second-person stories in Living Arrangements just poured out of me. The voices came through really strongly and I felt, at the time, that there was no other way to write those stories. But since Living Arrangements, I’ve largely left this point of view behind. I’m not saying that I’ll never write another story in second person again, but I’ve moved on for now.

I don’t know how to explain my POV decision-making process. I suppose it’s dictated by the character or a larger vision for the story itself. It just seems to happen organically for me.

7. I particularly enjoyed some of the strange turns your stories take, which crystallise the character for the reader. What do you ask yourself when you are halfway through a story? Do you usually know where you're headed or do things come together unexpectedly?

Many of the story endings in Living Arrangements surprised me as I was writing them. I love that. I’m not a writer who sits down and makes outlines and knows exactly what will happen. That’s the joy in writing for me – surprising myself and watching as the work takes over in ways I never imagined. I think I’m at my best when I’m not afraid to explore, let things happen, and maybe even get a little lost.

8. Some of your endings seem like soft landings but instead pack a hard punch during their evolution. There often seems to be an undercurrent of sexual danger, violence, the starkness of death. How do you feel when you finish a story? Do you revise a lot? Immediately or long afterwards? Have these stories undergone much rewriting and how long do you think it takes to get a story shipshape?

I revise in layers over a long period time. It’s like one big onion – layer after layer covered with a messy skin and causing lots of tears, not to mention all the bad metaphors that need to be cut (see: revision is like an onion). I will revise pieces over a period of years, but the drive to revise almost never goes away, even after publication. For example, I’d probably make changes to many of the Living Arrangements stories right now if I could. Having a book published is terrifying because you can’t make any more improvements, but it’s also a relief for the same reason – you can finally move on for good.

When I finish a draft of a story, I feel satisfied. I feel most like myself.

9. I'm not sure how you feel about this but I shy away from questions such as, Where do your characters come from? Or, Did this happen to you in real life? I prefer to let the work stand on its own. How do you feel about these questions?

Sometimes I kind of love it when people ask if something in my fiction happened in real life, (lauramaylenewalter.com) because then I get to tell them “No.” I find this really satisfying for some reason. Of course, it can also be frustrating, and I have to remind myself that this question isn’t really an attack on my imagination but rather just curiosity. And am I really going to complain that there are people out there who think I was once an elite figure skater or worked as a lingerie shop model? No. It’s hilarious.

10. Have you enjoyed book promotion so far? What has been your most fruitful experience? (And your most fruitless if there have been any?)

The words “book promotion” make me feel guilty because there’s probably so much more I could have done. They also make me want to lock myself in my writing room and avoid all interaction forever and ever and just write, but then I have to get over myself.

Blogging has probably worked best for me and has introduced a fair number of readers to my collection. (My mantra for the blog is “Don’t be boring or too promotional,” which I constantly try to live up to.) I’ve also written articles for Poets & Writers and other writing markets, which led some readers to Living Arrangements. Reviews help, too, but that’s largely out of my control. I’m not a big Twitter fan – I keep trying, but I’m just not – and I use Facebook primarily for personal reasons, not to promote my book. I get social media fatigue fairly easily and have found the blog is what interests me the most and is what I can do best.

11. Briefly, for those who haven't yet read your very earnest and cool blog, how does Laura Maylene Walter the blogger differ from Laura Maylene Walter the author?

The blogger is goofier, more self-deprecating, (lauramaylenewalter.com) and a lot drunker (lauramaylenewalter.com) than the author. I also try to take my husband’s advice when blogging, which is to “keep it real” at all times. Apparently, being true to myself on my blog means attempting really bad jokes and posting photos of my cats. (lauramaylenewalter.com) So be it! The author side of me, meanwhile, is quieter, more serious, and won’t shy away from writing about sex or politics like the blogger might.

Also, the blogger is willing to say, “Please buy Living Arrangements immediately” while the author just wants some quiet time alone with her cats and the writing desk.

Thanks so much Laura for answering my questions and I invite you all to order a copy of Living Arrangements.

Two foolhardy snowboarders challenge the savagery of mountain weather in the Dolomites. A Ghanaian woman strokes across a hotel pool in the tropics, flaunting her pregnant belly before her lover's discarded wife. 'Pelt' was longlisted in the Frank O'Connor International Short Story Award and Semi-Finalist in the Hudson Prize. 'Magaly Park' was Pushcart-nominated in 2014.

Monday, 17 December 2012

Friday, 23 November 2012

National Short Story Week: Late Views from Behind the Coffee Pot

As a writer whose first short story collection is being published next year it's hard to admit that National Short Story Week passed me by. I knew it was happening. I didn't attend any events in my neighbourhood (tiny village surrounded by roadworks and unfortunate Palladian villas on hills), mainly because there weren't any. I didn't even read up much, reply to anything, or even finish my own damn revisions (I did make the executive decision to remove two stories. Or maybe not. Or maybe.)

But I've been reading. This year I have read quite a few short story collections, more than I can write about here. The most recent have had me really thinking about what constitutes a great short story - as a reader - and trying (desperately!) to relate that to my own work. I finally concluded early one morning as the 5.50am alarm went off that the last line of a short story is like a gate being clicked shut, or a lock being snapped closed, or the final piece of a jigsaw being eased into place. It must be a moment of completion, of being locked within the story like a tight embrace.

Nothing new here, but it felt clarifying. I was just as thrilled when I read about Hemingway's iceberg theory - where 80% of the 'story' lies suggested beneath the surface. And now I have this warming nugget to add to my writerly thoughts.

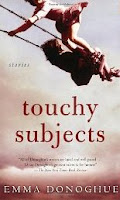

I'll start with the short story collection I am reading now, Irish Emma Donoghue's 'Touchy Subjects'. A lot of people say they don't particularly like short stories because as soon as you are absorbed, the action is over, the climax is behind your back, or shivering in your hands. Emma's stories are swift, almost casual, and difficult to put down. Each time I can feel that last jigsaw piece falling into place and I look forward to that resolution, the end of that compact journey. And yet her characters are no more compelling than you or I. A personnel officer places his chic coat over a homeless man, while ridden with moral fastidious doubts. A lesbian couple split up over a vet's bill. A man can't decide what colour to paint his house. And one of my favourites, a young guy struggles to tell his girlfriend about the hair on her chin. So artful. So cheeky.

Before that I read 'Dark Roots' by Australian author Cate Kennedy. What a mistress of the story! Cate's story 'Cold Snap' was in The New Yorker and it's easy to see why. A 'simple' country boy is treated as such by a city woman who has bought a house nearby, whose arrogance has her eliminate the old gum trees obstructing her lake view. The 'simple' narrator deals with this in a chilling way. Another favourite is the first story 'What Thou and I Did, Till We Loved'. It's almost too beautiful to explain but the essence of this and many of Cate's pieces is that outer action follows inner contemplation or compulsion. She rides that motion with scant language, speaking of relationships that change gears and the tight weave of domesticity. Strongly recommended.

Laura Maylene Walter is an American writer whose collection 'Living Arrangements' won the G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction. I 'met' Laura through a loose group of American writer/bloggers who I join when I can, and I've been reading her blog for ages (I will be interviewing Laura in the near future!). I knew from the tone of Laura's blog voice that I would enjoy her book and what a rewarding, thoughtful read, with many of her stories still making eddies in my head. Laura addresses loss and place, quirky women, beauty and survival, the dance between women and men, sometimes with a hint of danger. Her characters are often numb, pulling away from their pasts or their place in society. I liked the contrast, the stillness and the lack of fear in Laura's voice. Brilliant.

I read Sarah Hall's 'The Beautiful Indifference' while on a lounger in Corsica this summer on breezy afternoons. It finished too quickly. Having received deserved recognition last year, I knew this book was a banner-waver for short story writers and it didn't disappoint for a second. I haven't read Hall's novels - already someone with such an output at her age makes me green all over - but I wouldn't want my admiration for her stories to be turned into something else. Her stories were long and fruitful, drenching, draining, beautiful. From her EFG Booktrust short-listed 'Vuotjarvi' which takes place on the shores of a Finnish lake, to a lover's tiff gone super-bad in Maputo, involving - maybe - a leopard; Sarah delves deep into the sensual folds of coupledom, and cuts into British society. Her language is break-taking:'They had already rowed out..and gone in where the shadows were expansive, the bottom a black imagining.' If you buy this one, don't give it away.

Recently I read that the best stories are those that you might forget, but you remember. You remember the tones, the lilt of the language, the current of thought. These are all collections that I will be remembering.

But I've been reading. This year I have read quite a few short story collections, more than I can write about here. The most recent have had me really thinking about what constitutes a great short story - as a reader - and trying (desperately!) to relate that to my own work. I finally concluded early one morning as the 5.50am alarm went off that the last line of a short story is like a gate being clicked shut, or a lock being snapped closed, or the final piece of a jigsaw being eased into place. It must be a moment of completion, of being locked within the story like a tight embrace.

Nothing new here, but it felt clarifying. I was just as thrilled when I read about Hemingway's iceberg theory - where 80% of the 'story' lies suggested beneath the surface. And now I have this warming nugget to add to my writerly thoughts.

I'll start with the short story collection I am reading now, Irish Emma Donoghue's 'Touchy Subjects'. A lot of people say they don't particularly like short stories because as soon as you are absorbed, the action is over, the climax is behind your back, or shivering in your hands. Emma's stories are swift, almost casual, and difficult to put down. Each time I can feel that last jigsaw piece falling into place and I look forward to that resolution, the end of that compact journey. And yet her characters are no more compelling than you or I. A personnel officer places his chic coat over a homeless man, while ridden with moral fastidious doubts. A lesbian couple split up over a vet's bill. A man can't decide what colour to paint his house. And one of my favourites, a young guy struggles to tell his girlfriend about the hair on her chin. So artful. So cheeky.

Before that I read 'Dark Roots' by Australian author Cate Kennedy. What a mistress of the story! Cate's story 'Cold Snap' was in The New Yorker and it's easy to see why. A 'simple' country boy is treated as such by a city woman who has bought a house nearby, whose arrogance has her eliminate the old gum trees obstructing her lake view. The 'simple' narrator deals with this in a chilling way. Another favourite is the first story 'What Thou and I Did, Till We Loved'. It's almost too beautiful to explain but the essence of this and many of Cate's pieces is that outer action follows inner contemplation or compulsion. She rides that motion with scant language, speaking of relationships that change gears and the tight weave of domesticity. Strongly recommended.

Laura Maylene Walter is an American writer whose collection 'Living Arrangements' won the G.S. Sharat Chandra Prize for Short Fiction. I 'met' Laura through a loose group of American writer/bloggers who I join when I can, and I've been reading her blog for ages (I will be interviewing Laura in the near future!). I knew from the tone of Laura's blog voice that I would enjoy her book and what a rewarding, thoughtful read, with many of her stories still making eddies in my head. Laura addresses loss and place, quirky women, beauty and survival, the dance between women and men, sometimes with a hint of danger. Her characters are often numb, pulling away from their pasts or their place in society. I liked the contrast, the stillness and the lack of fear in Laura's voice. Brilliant.

I read Sarah Hall's 'The Beautiful Indifference' while on a lounger in Corsica this summer on breezy afternoons. It finished too quickly. Having received deserved recognition last year, I knew this book was a banner-waver for short story writers and it didn't disappoint for a second. I haven't read Hall's novels - already someone with such an output at her age makes me green all over - but I wouldn't want my admiration for her stories to be turned into something else. Her stories were long and fruitful, drenching, draining, beautiful. From her EFG Booktrust short-listed 'Vuotjarvi' which takes place on the shores of a Finnish lake, to a lover's tiff gone super-bad in Maputo, involving - maybe - a leopard; Sarah delves deep into the sensual folds of coupledom, and cuts into British society. Her language is break-taking:'They had already rowed out..and gone in where the shadows were expansive, the bottom a black imagining.' If you buy this one, don't give it away.

Recently I read that the best stories are those that you might forget, but you remember. You remember the tones, the lilt of the language, the current of thought. These are all collections that I will be remembering.

Saturday, 20 October 2012

Up Close and Personal

I have spent the past few weeks wrestling with my short story collection, due out next year. I've yet to decide on story order, although story precedence seems to be falling into place. I've also had feedback from some very generous readers - some of whom have thrown my thinking on its head. As the stories voyage from Africa to Europe and back, vastly different environments are drawn up, sketching characters who deal with their appearance or physical foibles or fixations, in shifting contexts coloured by history and landscape.

I've also been reading up on what other writers have said about trying to stitch up a collection. It's rarely comfortable reading, because there are so many elements, so many different opinions. What to aim for - a vast and diverse collection, or a thematic voyage through interlinked characters? A parade of stand-alone stories (I can think of Nam Le's 'The Boat') or a tessellated piece like Gretchen Shirm's 'Having Cried Wolf'. And, is the story collection a prelude to the more imposing authorial task of the novel, or is it art unto itself?

So many tussles going on. And this poor writer's pieces go from gay druggies in Berlin to a story of incest in Sekondi, Ghana. How to map these out without losing/baffling the reader?

And yet, as one of my readers said and some of the discussions I read confirmed, short stories are meant to be reread, fished through, digested and thought about. They sit on the stomach. They smoulder in the mind. They are not a comfy flow from one snatch of free time to the next, the connected world of the chunky novel that gives the reader relief. Rather they are demanding, feisty, often unresolved and can leave you sorely wanting. Cliff-hangers, in their most effective form, with the crux of the story's reality just beyond reach, the story around the story, leading the reader up a garden path that buzzes with suggestion.

If you are a short story writer or interested in how these collections come about, do read this discussion, one of the most pertinent series of points I've come across lately www.twentyone.org.uk/issue1/cox.html.

Some of the most interesting points include:

..Publishers favour the linked collection, especially if they can disguise it as a novel. If that isn't possible, they may still suggest a unitary title. This is how Mothers and Sons was given its title, homogenising Tòibin's wide-ranging collection, and privileging one theme among many.

..However tenuous the links may be, story cycles and thematic collections are highly visible, and they are popular with both publishers and literary critics.

..How do you go about assembling all those bits and pieces into a book-length manuscript? Do you just put your best stories together and hope for the best? Or is there some inner logic?

And, for me, one of the most resonant point of all:

..A short story doesn't really resolve anything. It sustains tension, which is probably another reason why people don't take it to the beach. It's not a relaxed form. It can mirror a confusion which doesn't have to go away.

..The word story, the word plot, means a crisis, a conflict, an escalation and then a resolution. Resolution can be a positive, reassuring, warm resolution, but it can also be a kind of Shakespearean, apocalyptic resolution. The short story does have a lot more of the latter - confusing resolution, resolution that turns everything on its head - but it's still a type of closure, a truth slamming down on the reader.

This entire piece is worth reading and is called Oceans of Stories: Collections, Sequences and the Short Story. The discussion is chaired by Ailsa Cox, of the Edge Hill Prize, and the speakers included Anthony Delgrado (bluechrome), Ra Page (Comma Press), Duncan Minshull (BBC Radio 4). Very glad I discovered this.

And this is the bit where most short stories writers photograph their post-its on the floor or the bed, showing you how maddeningly off their rockers they are. Check this out. Can betrayed Laila rub shoulders with broken Sebastien in Brussels? Will Nathalie lead on to Veronique and her contemplation of scarred Heinrik? Will Celeste stand back and allow her brother and his lover to take their own lives?

I read a beautiful comment by Scott Prize winner Carys Bray. She said that unconsciously, she had bookended her collection with two similar pieces. I was thrilled to discover a while back that I had done the same thing too - 'Pelt' starts with a feisty pregnant woman determined to win her man back, 'Volta' ends with another, completely flawed pregnant woman about to lose hers.

I've also been reading up on what other writers have said about trying to stitch up a collection. It's rarely comfortable reading, because there are so many elements, so many different opinions. What to aim for - a vast and diverse collection, or a thematic voyage through interlinked characters? A parade of stand-alone stories (I can think of Nam Le's 'The Boat') or a tessellated piece like Gretchen Shirm's 'Having Cried Wolf'. And, is the story collection a prelude to the more imposing authorial task of the novel, or is it art unto itself?

So many tussles going on. And this poor writer's pieces go from gay druggies in Berlin to a story of incest in Sekondi, Ghana. How to map these out without losing/baffling the reader?

And yet, as one of my readers said and some of the discussions I read confirmed, short stories are meant to be reread, fished through, digested and thought about. They sit on the stomach. They smoulder in the mind. They are not a comfy flow from one snatch of free time to the next, the connected world of the chunky novel that gives the reader relief. Rather they are demanding, feisty, often unresolved and can leave you sorely wanting. Cliff-hangers, in their most effective form, with the crux of the story's reality just beyond reach, the story around the story, leading the reader up a garden path that buzzes with suggestion.

If you are a short story writer or interested in how these collections come about, do read this discussion, one of the most pertinent series of points I've come across lately www.twentyone.org.uk/issue1/cox.html.

Some of the most interesting points include:

..Publishers favour the linked collection, especially if they can disguise it as a novel. If that isn't possible, they may still suggest a unitary title. This is how Mothers and Sons was given its title, homogenising Tòibin's wide-ranging collection, and privileging one theme among many.

..However tenuous the links may be, story cycles and thematic collections are highly visible, and they are popular with both publishers and literary critics.

..How do you go about assembling all those bits and pieces into a book-length manuscript? Do you just put your best stories together and hope for the best? Or is there some inner logic?

And, for me, one of the most resonant point of all:

..A short story doesn't really resolve anything. It sustains tension, which is probably another reason why people don't take it to the beach. It's not a relaxed form. It can mirror a confusion which doesn't have to go away.

..The word story, the word plot, means a crisis, a conflict, an escalation and then a resolution. Resolution can be a positive, reassuring, warm resolution, but it can also be a kind of Shakespearean, apocalyptic resolution. The short story does have a lot more of the latter - confusing resolution, resolution that turns everything on its head - but it's still a type of closure, a truth slamming down on the reader.

This entire piece is worth reading and is called Oceans of Stories: Collections, Sequences and the Short Story. The discussion is chaired by Ailsa Cox, of the Edge Hill Prize, and the speakers included Anthony Delgrado (bluechrome), Ra Page (Comma Press), Duncan Minshull (BBC Radio 4). Very glad I discovered this.

And this is the bit where most short stories writers photograph their post-its on the floor or the bed, showing you how maddeningly off their rockers they are. Check this out. Can betrayed Laila rub shoulders with broken Sebastien in Brussels? Will Nathalie lead on to Veronique and her contemplation of scarred Heinrik? Will Celeste stand back and allow her brother and his lover to take their own lives?

I read a beautiful comment by Scott Prize winner Carys Bray. She said that unconsciously, she had bookended her collection with two similar pieces. I was thrilled to discover a while back that I had done the same thing too - 'Pelt' starts with a feisty pregnant woman determined to win her man back, 'Volta' ends with another, completely flawed pregnant woman about to lose hers.

Sunday, 9 September 2012

Abuse

On Wednesday I took my second son to see the great Kenyan writer Ngugi Wa Thiong'o speak at the Mantova Literary Festival. Ngugi spoke with wisdom and - we thought - restraint about the neo-colonial state of the African continent. A key sentence in his talk was that 'Africa has given, much more than she has received'.

I wondered how many times Ngugi has said this to a fusty, literary-minded audience. Africa has given. I thought it an extremely polite way of saying, African has been stolen from since the days of Adam! In fact, when he said that 'European modernity has African colonisation at its centre', I felt like cheering. Rather over-enthusiastic of me, but let this old Africa-head explain. My favourite university course, years ago, was Modern African and Asian History - Independence Movements and the Struggle Against Imperialism, and after thirteen years in East and West Africa my favourite conversations still deal with the rich cultural and economic force that is contemporary Africa.

But - not surprisingly - there was silence when Ngugi spoke these wise words. We sat there frowning and nibbling our nails, thinking of the great writer in a prison cell devising his lauded novel. So humbling for this middling writer with a computer screen and constant electricity. And no police detention likely for the material she is writing!

Ngugi - gingerly - also warned the mainly Italian audience about the widespread hostility towards African refugees arriving on shoddy boats, half of which sink in the rough seas off Lampedusa. He asked, Why are people afraid, given Europeans have migrated to every corner of the globe for centuries? Why?

It made me think of so many stories about this new wave of immigration. Stories of how people's humanity caves in because of these age-old inbuilt fears. A Ghanaian truck driver friend, whose truck broke down on an Austrian highway in the middle of winter. He sat waiting for help for eight hours. A Nigerian-Italian lass, brought up in this country, who lost her job at a bakery because people wouldn't buy the bread she touched.

And yet, it also made me think how that hostility is terribly two-faced.

Just a week back I had a dear friend - from West Africa - sitting at my kitchen table with a beer, all het up. She is tired of Italy. She is tired of the beckoning hands that pop out of cars on a city street, in the morning, often when she has just dropped her small kids at school. Vieni, vieni quà, how much bella? And today, she is furious because her landlord, called in to check a fusebox, suddenly fondled her breasts and buttocks. A man who knows her husband, who gives toffee to her kids.

'Ah! And he just laughed!' she says. He thought it was just a joke, just a little thing. A prod here, a caress there, skin on skin.

Africa may have given for centuries, but the next day my furious friend told me that she belted back on her landlord's door. At lunchtime, a sacred hour, when all the family gather. Her landlord answered.

Hello? Buongiorno! Shall I have my husband fondle your wife's breasts? Or touch your daughter's bottom??

The man was horrifed.

I wondered how many times Ngugi has said this to a fusty, literary-minded audience. Africa has given. I thought it an extremely polite way of saying, African has been stolen from since the days of Adam! In fact, when he said that 'European modernity has African colonisation at its centre', I felt like cheering. Rather over-enthusiastic of me, but let this old Africa-head explain. My favourite university course, years ago, was Modern African and Asian History - Independence Movements and the Struggle Against Imperialism, and after thirteen years in East and West Africa my favourite conversations still deal with the rich cultural and economic force that is contemporary Africa.

But - not surprisingly - there was silence when Ngugi spoke these wise words. We sat there frowning and nibbling our nails, thinking of the great writer in a prison cell devising his lauded novel. So humbling for this middling writer with a computer screen and constant electricity. And no police detention likely for the material she is writing!

Ngugi - gingerly - also warned the mainly Italian audience about the widespread hostility towards African refugees arriving on shoddy boats, half of which sink in the rough seas off Lampedusa. He asked, Why are people afraid, given Europeans have migrated to every corner of the globe for centuries? Why?

It made me think of so many stories about this new wave of immigration. Stories of how people's humanity caves in because of these age-old inbuilt fears. A Ghanaian truck driver friend, whose truck broke down on an Austrian highway in the middle of winter. He sat waiting for help for eight hours. A Nigerian-Italian lass, brought up in this country, who lost her job at a bakery because people wouldn't buy the bread she touched.

And yet, it also made me think how that hostility is terribly two-faced.

Just a week back I had a dear friend - from West Africa - sitting at my kitchen table with a beer, all het up. She is tired of Italy. She is tired of the beckoning hands that pop out of cars on a city street, in the morning, often when she has just dropped her small kids at school. Vieni, vieni quà, how much bella? And today, she is furious because her landlord, called in to check a fusebox, suddenly fondled her breasts and buttocks. A man who knows her husband, who gives toffee to her kids.

'Ah! And he just laughed!' she says. He thought it was just a joke, just a little thing. A prod here, a caress there, skin on skin.

Africa may have given for centuries, but the next day my furious friend told me that she belted back on her landlord's door. At lunchtime, a sacred hour, when all the family gather. Her landlord answered.

Hello? Buongiorno! Shall I have my husband fondle your wife's breasts? Or touch your daughter's bottom??

The man was horrifed.

Saturday, 1 September 2012

Corsican escape

For years I spent my summers here in my elegant farmhouse watering tomatoes, weeding my zucchinis, making apricots flans, entertaining Sunday guests and ferrying intercontinental friends to chic exhibitions in Venice and Verona.

Then I went camp.

I mean, yes I did a stint in Berlin with some gay pals who do feature in one of my short stories and yes I did do a lot of kinky clubs as an observer... But then my friend's dog I used to dogsit died and it was suggested I join the clan of friends, exes, somewhat cousins and live dogs, for their annual camping trip to Corsica.

I did last year. And I did again this year.

The island is so beautiful. I think I should set a novel there, or it seems suited to a steamy novella perhaps. I could rent a room in a village in the hills set back from the sea, with stone paths and iron ballustrades and keening churches with scrolled white facades. I could swim early in the mornings, hike home to my shadowed room, work at length without internet, without kids, until pastis at midday.

Then, after lunch and coffee at the bar or the lady's downstairs, I could go back to my room, recharged, and as the afternoon sun moved about in boxes I could continue on, undisturbed, sentence after sentence, scene after scene.

Oh, dream on!

But I do. The evenings in the bar with its semi-circular terrace over the outstretched bay, which you wouldn't have to visit, except briefly to the shops or the pretty markets, or - dread! - to check your mail. Or yes, to meet friends passing through and urging to join a hike through the arid mountainous centre or a visit to a special pebbly beach - no way but thanks! And then hurry back.

It would be so good.

This summer the sea has been tickling my fancies. First in Cornwall with its cawing seagulls and green coasts and me nearly tripping over a pirate in the street. And then in Corsica with her fiery interior and scorched shores, tinkering jade water up my torso.

Maybe next summer. A Room of My Own? Instead of a sandy tent and fifteen Italians at lunch, buckets of rosé and a tub of washing up??

I am so tempted.

Then I went camp.

I mean, yes I did a stint in Berlin with some gay pals who do feature in one of my short stories and yes I did do a lot of kinky clubs as an observer... But then my friend's dog I used to dogsit died and it was suggested I join the clan of friends, exes, somewhat cousins and live dogs, for their annual camping trip to Corsica.

I did last year. And I did again this year.

The island is so beautiful. I think I should set a novel there, or it seems suited to a steamy novella perhaps. I could rent a room in a village in the hills set back from the sea, with stone paths and iron ballustrades and keening churches with scrolled white facades. I could swim early in the mornings, hike home to my shadowed room, work at length without internet, without kids, until pastis at midday.

Then, after lunch and coffee at the bar or the lady's downstairs, I could go back to my room, recharged, and as the afternoon sun moved about in boxes I could continue on, undisturbed, sentence after sentence, scene after scene.

Oh, dream on!

But I do. The evenings in the bar with its semi-circular terrace over the outstretched bay, which you wouldn't have to visit, except briefly to the shops or the pretty markets, or - dread! - to check your mail. Or yes, to meet friends passing through and urging to join a hike through the arid mountainous centre or a visit to a special pebbly beach - no way but thanks! And then hurry back.

It would be so good.

This summer the sea has been tickling my fancies. First in Cornwall with its cawing seagulls and green coasts and me nearly tripping over a pirate in the street. And then in Corsica with her fiery interior and scorched shores, tinkering jade water up my torso.

Maybe next summer. A Room of My Own? Instead of a sandy tent and fifteen Italians at lunch, buckets of rosé and a tub of washing up??

I am so tempted.

Thursday, 2 August 2012

A Literary Festival Virgin

For a while there I felt it. Stinging pain, embarrassment. Worry that I wouldn't be able to perform.

Beforehand, I worried that my clothes would be all wrong, that my hands would fidget, that my mouth would say awful things.

Last week I spoke at my first literary festival in Penzance.

I watched other old hands breeze onto the stage, sip their water, cross and uncross their legs. I listened to their unburdened discourses, the ease with which they shared their characters, their writing processes, the anecdotes rolling out as if on a whim.

It made me nauseous. It made me want to run away.

A few days earlier I spoke to a friend who is a pop star, can you believe? Her advice: Be Exuberant. So that day, my day, I heeled up the hill feeling gleefully, painfully, horribly Exuberant.

Strangely, it was fine. It seems my body was two steps ahead of my thoughts and saw to it that I was just a tinge nervous, and not smiling too hard. I did not trip onto the stage. Or even sweat much. The other writers for my session were marvellous and my unease dropped away. I too sipped my water and raised some light laughter.

I came out on a rocking high!

I would like to think that, for once, everything came together. I knew why I was doing this. Why I was sitting on a stage with people looking up at me, all expectant, warm, wanting to laugh or look out the window, or thinking perhaps they should have gone to the loo. It felt good, funny, enlivening. Can you believe I want to do more? In September I am up for another one - the Women's Fiction Festival in Matera. I know I will be a little nervous as it will be in Italian. But as well as nervous I will be keen, curious, alive. I've come this far.

Outside my window in Penzance I had a peaceful view. Just walls and yards and houses. Sometimes a big golden dog barked or moved about on the stones. I worked. For four days - not before having a scrumptious Cornish breakfast each morning - I felt pure concentration. No phone calls, no homework, no taxi-driving, no worrying (should I feel guilty about this?), no guilt. The short story revision has lagged. Promotion of my novel has taken up enormous slabs of time and energy. But for a few good days I had my stories mapped on the bed, a new order in place, a rush of underlinings and crosses for a new print-out, and a damned fine view through the afternoon.

I also met other writers, such as Alison Lock, poet and short story also with Indigo Dreams who, like me, is spanning genres and wondering what comes next. I imagine this is the true purpose of Literary Festivals, just like some people go to the beach. Instead of dissolving into sand, into water, into the whole coastal experience, we writers speak of words, share hopes and defeats, gossip a bit and, best of all, start itching to go back to work.

A lovely gift: today my copy of Tears in the Fence arrived, with my story 'Veronique in the Dark' which is part of the collection. I reread it in a sushi bar waiting for my son to arrive.

By late autumn Veronique called Heinrik. She had recommenced work and her injury was no longer the thing she had to manouvre around. The light had distilled, as though winter had chosen her course and would visit their city when she pleased.

Beforehand, I worried that my clothes would be all wrong, that my hands would fidget, that my mouth would say awful things.

Last week I spoke at my first literary festival in Penzance.

I watched other old hands breeze onto the stage, sip their water, cross and uncross their legs. I listened to their unburdened discourses, the ease with which they shared their characters, their writing processes, the anecdotes rolling out as if on a whim.

It made me nauseous. It made me want to run away.

A few days earlier I spoke to a friend who is a pop star, can you believe? Her advice: Be Exuberant. So that day, my day, I heeled up the hill feeling gleefully, painfully, horribly Exuberant.

Strangely, it was fine. It seems my body was two steps ahead of my thoughts and saw to it that I was just a tinge nervous, and not smiling too hard. I did not trip onto the stage. Or even sweat much. The other writers for my session were marvellous and my unease dropped away. I too sipped my water and raised some light laughter.

I came out on a rocking high!

I would like to think that, for once, everything came together. I knew why I was doing this. Why I was sitting on a stage with people looking up at me, all expectant, warm, wanting to laugh or look out the window, or thinking perhaps they should have gone to the loo. It felt good, funny, enlivening. Can you believe I want to do more? In September I am up for another one - the Women's Fiction Festival in Matera. I know I will be a little nervous as it will be in Italian. But as well as nervous I will be keen, curious, alive. I've come this far.

Outside my window in Penzance I had a peaceful view. Just walls and yards and houses. Sometimes a big golden dog barked or moved about on the stones. I worked. For four days - not before having a scrumptious Cornish breakfast each morning - I felt pure concentration. No phone calls, no homework, no taxi-driving, no worrying (should I feel guilty about this?), no guilt. The short story revision has lagged. Promotion of my novel has taken up enormous slabs of time and energy. But for a few good days I had my stories mapped on the bed, a new order in place, a rush of underlinings and crosses for a new print-out, and a damned fine view through the afternoon.

I also met other writers, such as Alison Lock, poet and short story also with Indigo Dreams who, like me, is spanning genres and wondering what comes next. I imagine this is the true purpose of Literary Festivals, just like some people go to the beach. Instead of dissolving into sand, into water, into the whole coastal experience, we writers speak of words, share hopes and defeats, gossip a bit and, best of all, start itching to go back to work.

A lovely gift: today my copy of Tears in the Fence arrived, with my story 'Veronique in the Dark' which is part of the collection. I reread it in a sushi bar waiting for my son to arrive.

By late autumn Veronique called Heinrik. She had recommenced work and her injury was no longer the thing she had to manouvre around. The light had distilled, as though winter had chosen her course and would visit their city when she pleased.

Wednesday, 6 June 2012

Tug Boats

It's time to turn around. My women's commercial novel is out. I have a book under my belt. Reviews have been thoughtful and rewarding (mostly), and I've stopped reading them. I am peddling - the peddling required if a book is to make any headway - but I'm hoping a grassroots campaign will take hold. In the meantime I am allowed to turn back to the short story collection coming out next year. I am revising and editing. Easier than a novel in the sense that most of the stories have been published so they have been clarified and worked over. But it's never enough, I've learned. Editing is a microscopic process, requiring various lenses, clear lighting, a tense kinked neck.

But I'm up for it. The stories in their wide range of locations and subject matter provide a new home for my thoughts, both elated and bruised by the uncertainty of publication, and the greater uncertainty of sales in a cold, multinational-slapped world. It's quite a relief to come back to the silent, word-crammed page. No other voices from beyond, no pressure to reply, just the words of my stories. Bright polished stones looking for attention and company.

PS I am reading Deborah Robertson's delicate and compelling novel of stories, Careless. It tugs me back to Australia.

But I'm up for it. The stories in their wide range of locations and subject matter provide a new home for my thoughts, both elated and bruised by the uncertainty of publication, and the greater uncertainty of sales in a cold, multinational-slapped world. It's quite a relief to come back to the silent, word-crammed page. No other voices from beyond, no pressure to reply, just the words of my stories. Bright polished stones looking for attention and company.

PS I am reading Deborah Robertson's delicate and compelling novel of stories, Careless. It tugs me back to Australia.

Friday, 6 April 2012

A Lost City and Photo of Haji Nur

I didn't really mean for this blog to become an Africa-vent for me. The short stories in the Pelt collection are varied. Some are set in Europe or Australia. Some are set in Africa and travel close to the seam of my life. One is set in Somalia, for example, where I was a young wife without a clue how to mother.

I didn't really mean for this blog to become an Africa-vent for me. The short stories in the Pelt collection are varied. Some are set in Europe or Australia. Some are set in Africa and travel close to the seam of my life. One is set in Somalia, for example, where I was a young wife without a clue how to mother. The other night I felt a jarring when I saw my old street in Mogadishu on the news. There had a been a bombing at the National Theatre of Xamar, whose whining singers used to go on and on into the night, almost until the morning muezzin. I saw the junction where twenty years ago a cunning thief put his hand into our jeep and stole my young husband's glasses. I saw the hill we used to chug up to our turn-off, a rutted dirt road where one evening we found a blabbering man, an ex-soldier, who used to live in our street. He had fought in the Ogaden border world and lost his senses, his family, and years of his life.

I don't think of Somalia often except in bursts of guilty pain. It was my first foray out of Europe, the first strange tongue I began to learn beyond the European languages I'd learnt in high school, the first African capital I explored on foot with a driver who was as skinny as myself. It was the first time I ever had help in the house, slow Faduma who pasted magazine cut-outs on our walls and cooked fermented bread like pads of white earth.

The guilty pain comes because I wonder. I don't know what happened to my co-secretaries from the office. It was pre-internet, we left in a rush when Siad Barre's young quat-chewing soldiers took the centre, claimed cars, killed and raided houses. I don't know what happened to the children my friends were trying to raise, or those who came after in their complex and - for Westerners - uneven marriages. I just don't know. Every time I see a tall Somali man and recognise their gutteral language I don't know what to think - was he a man who as a young soldier shot at women in a market? Or a man who truly wants to harvest peace for the future?

I remember my first-born receiving his first vaccination in a filthy clinic that made me grimace. I told myself, be equal, your son is living here - quite a joke given we were able to escape. I remember the tough exterior of Somali women colleagues, so fragile and damaged inside. I remember the flat rooftop of our old Italian-built house with the spiral staircase, watching an eclipse of the moon with our watchman Elmi, the way the city cascaded down towards the sea.

Elmi was gunned down by troops soon after we left.

Tuesday, 6 March 2012

On the road, always

Last year a friend nearly fell over his feet when I said I hadn't read Jack Kerouac's classic 'On the Road'. Shamefully, I had not. Not even when I left my continent at 21-and-a-day, never to return, a woman who's been on the road for decades.

Last year a friend nearly fell over his feet when I said I hadn't read Jack Kerouac's classic 'On the Road'. Shamefully, I had not. Not even when I left my continent at 21-and-a-day, never to return, a woman who's been on the road for decades. So I ordered a copy on Amazon and read it into the night.

For those of you who read Kerouac at the appropriate age - I would say an itchy-footed nineteen - I'm sure the book held its allure. I probably would have fallen for its powerful flux of restless movement, moneyless, sex and young love under endless starry skies. And its gaudy untempered language, the rush of it.

But as a post-40 year old who has done a lot of moving around, given birth in a third world hospital, gotten lost in deserts, been moneyless in Bamako and other assorted places, had AIDs victims in the household, Kerouac's book didn't make me feel like overturning the boat. Throughout, I was conscious of Kerouac's landmark style, an albatross that almost condemned him to early death through alcohol abuse - that I adored. But his restlessness became irritating early on, as well as his young self-centredness. As I read I couldn't help wondering how his writing style might have expanded and his subject matter deepened as he reached middle age, as his excitability ebbed and his inwardness changed shape.

That was what I wanted. I even wondered if the guy who suggested the book had remained braked in his twenties, imploded and repressed, unable to grow up.

As I have moved I have written diaries, but these diaries are tied together, locked in a cupboard, for no eyes to see. They are private. What I was searching for in Paris at twenty, as I cropped my hair and grew skinny and did the Lolita with older men, I no longer wish to know. I remember one summer I hired a car and drove it around France, from top to bottom, stopping at every town looming on the flat horizon, examining haunted Gothic cathedrals with the passion of a young woman with a shoddy colonial past. On one occasion I remember buying strawberries from a market, knocking on a man's door to open a bottle of wine, and stretching out in my bikini in a field full of cows.

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

Cartography

Back in the 90s I was a diplomat's wife about to go into existential crisis. But before I did (there is always lots of writing material in any sort of crisis), I wrote this story. It was when I belonged to the bitchy French Ambassadors' Wives Literary Club. It was when I wore linen suits to cocktail parties. It was when I hadn't even tried local Ghanaian food, nor eaten with my hands, nor driven around that hot rich country except in a convoy of diplomatic corps vehicles that were never flagged down.

Back in the 90s I was a diplomat's wife about to go into existential crisis. But before I did (there is always lots of writing material in any sort of crisis), I wrote this story. It was when I belonged to the bitchy French Ambassadors' Wives Literary Club. It was when I wore linen suits to cocktail parties. It was when I hadn't even tried local Ghanaian food, nor eaten with my hands, nor driven around that hot rich country except in a convoy of diplomatic corps vehicles that were never flagged down.I didn't fit well in that arid world of shimmering swimming pools, gardeners bent over lawns, whispering house staff. Nor with the French Ambassadors' Wives who took their dinner parties so seriously; their charity events, their art purchases.

It amazed me how people who I knew were ordinary in Europe, who pushed their own shopping trolleys, looked for specials along supermarket aisles and took out their own garbage under the moon, were able to hoist themselves above a whole society of people, a nation where they were guests.

After my crisis that changed. And so did my stories. But this one belongs to that period. It was picked out, I don't even remember how, by Virago, and placed in an anthology of women writers called 'Wild Cards'. I still remember walking down Shaftsbury Avenue with my new lover and baby, and seeing the book jacket in the window. Colossal, beaming pride.

This month Cartography is Story of the Month on www.inktears.com, and it will be part of my collection 'Pelt and Other Stories' coming out next year. It makes me think of cool nights, friction, skin.

If Della had never walked into that café in Stuttgart looking for her German-loving friend Stacey Mahler she would never have ended up at the bar with Luce and his odd, leggy son. Luce who was leaving for West Africa in a week; Luce who said There are other worlds while exerting a take-it-or-leave it pressure on her knee. Della wrote to Stacey a month later from the rainy season, half-deluded by the stinking multifarious setting, half-drenched by Luce’s unfiltered sexual coaching. What Della had been told afterwards was that Luce’s thirty-six-year-old wife Chanel had perished in a plane crash on a runway in northern Nigeria. If Della had siphoned off moments of the tragedy to crystallise her own mortality, she was also conscious of being a fast substitute. Uneasy, beyond her climax of flames and metal she might think: Luce had made love to a woman who had died.

Wednesday, 1 February 2012

The Year of the Short Story

I heard it on the blogvine. That 2012 is the Year of the Short Story. Did you know? This makes me thrilled for two reasons. First because my short story collection has been accepted for publication and will be coming out with this spirit in the air (sadly not till 2013 – I have my debut novel on my other plate!), and next and more roundly because it will increase the standing of this accessible but tricky form.

I heard it on the blogvine. That 2012 is the Year of the Short Story. Did you know? This makes me thrilled for two reasons. First because my short story collection has been accepted for publication and will be coming out with this spirit in the air (sadly not till 2013 – I have my debut novel on my other plate!), and next and more roundly because it will increase the standing of this accessible but tricky form.As a young thing I never wanted to study writing. Didn’t want to have my ideas pushed into shape. I was devoted to Katherine Mansfield, whose shimmering stories I think we should still go back to read. To feel the lightness of a beautifully seamed work, its spilling cloth and crafted movement. To travel quickly grasping the writer’s knowing hand. To feel pulse, labour, precision.

I’m sure so many short story writers have heard it all before – the marvels of the short story, with sudden gusto brought forth by big publishing companies while many have toiled long into the night with smaller publishing companies, or independents, or in self-publishing. But surely there is still reason to celebrate, to dress up and come to the party, wearing an extravagant pair of heels?

I’ll be there. Etherbooks have just put up two more stories of mine on www.etherbooks.com. For the unconvinced, my story ‘Innocent’ is free. Try this for size: Flemish aid worker Toby Vlaminck deals with a kleptomaniac driver wearing Peter Fonda sunglasses.

The Year of Well-Written Wonders.

Friday, 20 January 2012

The day the Klan came to Italy

Recently we've been talking about race at home. And today a blog posted by a friend made me remember a particular incident that in its warped way became educational.

My kids grew up on the old Gold Coast, today's Ghana, a country where slavery has a lengthy and even current history. I mentioned the slave forts in my last post, and while not wanting to linger in those cold dungeons I will mention standing in the pit, looking up to where it was said the governor had a wooden walkway installed, so as to look down for the prettiest captive. It was said that a woman who became with child became a freed woman: she did not have to crouch and grovel along the tunnel called 'the gate of no return'.

One of the things about being white in Ghana, apart from sunburn and never being able to be invisible, nor wear swishing local fabrics with any sort of stylishness, was that one often felt one represented the evil conqueror, the culture of the slavers, the scramble for Africa, the whole school of European thinking about the 'noble savage', the many wars of independence, today's neo-colonial wars of mineral wealth and mercenaries...

A heavy burden. But it was my fault. I studied Lenin's Theory of Imperialism in university, where I learned that capital sought new markets in order to refurbish its greedy mechanisms. I also studied African and Asian Independence Movements and in my innocent way fell in love with Isak Dinesen's beautiful opening words, 'I had a farm in Africa' (years after I went to her homestead - not the one used in the film - with a hostile guide who made me feel every bit the Dane handing out sticking plasters and paracetamol).

But back to my educational incident. For I could go on endlessly about the friction between cultures, the discomfort of history, the stories, the stories. The ancestors of today's Ghana were sent off in slave ships to the Americas. Somehow, my half-Ghanaian kid hasn't seriously studied this in school yet, Italian school I might add. They do the Civil Rights Movement, but history, which he fortunately loves, is seriously euro-centric. Perhaps that is why he made this discovery in a school friend's bag he brought home by mistake. It was around Halloween time, everyone was thinking parties, pumpkins. Masks.

My kid pulled out a triangular white cone of cloth with three holes in it. The rest of us, his older siblings, sat there staring. My youngest called out What is it? What's wrong? Slowly, we explained to him. About the raids in the bush. About the men and women chained together, families broken, never to see each other again. About the long congested journey over the oceans with the stench of death.

What type of mother handstitches a child's Halloween mask from this type of terror and cruelty? What type of idiotic being?

I used to fight battles verbally. Charge up to people. Seek justice. Rant and rave. In Africa I learnt how to fight. But strangely, my older kids calmed me. Told me how dumb these people were, how rich. That didn't stop me going to the school and having them labelled, showing my outrage. Seething.

God knows that ignorant woman had better never cross my path.

Friday, 13 January 2012

Infection

Years ago I wrote a story. It was the first time I tried to write anything after our return from Ghana. We had moved into a frigid old house in the middle of fields, the fog low upon us, rudimentary heating and the occasional country mouse. It was hard. If I thought living in the tropics was hard - malaria, thieves, power cuts, no water - I had no idea.

Eventually I pulled myself together and started to write. I was inspired by a postcard I had for some reason attached above my bed. It showed the Princes Town Fort along the Western Region coast, originally built by a Brandenburg Prince with stones imported from Prussia. It would have been the last construction seen by many a terrified slave sent across the Atlantic.

Along the sea there are several of these forts, evil bastions set among the coconut palms. Though they are frilled with fishing boats and market mammies and gleeful children, they are cruel to the core, chilly inside, burdened with enraged and frightened souls.

I don't know why I kept the postcard. We only visited that area a few times, and there were other more extensive structures at Cape Coast and Elmina where we took visitors to see the museums. This was a smaller, quieter place. But mouldy and dark; cruel. Deep down I suspect that is why I put that postcard on the wall in those early days. I had just been through a long period of cruelty, a grave injustice, a situation I never thought I would escape.

My story was originally long. Too long, too loaded. A failed son of the old regime comes back to Ghana to his hometown near the fort to witness his half-sister's last days. Her body is devoured by AIDS. His cranky mother wants the young woman's shame banished from the house. Eugene, my character, does not know how to act in this contemporary African society whose traditions he has not absorbed from birth. He is British-educated, a visitor here, only able to see so far.

Now, 'Infection' is up for publication with a prestigious magazine next year, and is part of my collection Pelt and Other Stories, the contract for which I excitedly signed this week.

Somehow, that story is my escape.

* * * *

Read my interview on http://womensfictionwriters.wordpress.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)